Points of Light

It started 50 years ago this year. In 1964 two 22 year old Peace Corp Volunteers, (PCV’s) married for less that 24 hours found themselves in PC training for a TB/Public Health project in Nyasaland. This was not their idea. Although they had wanted to go to Africa, they thought they would be placed, a married couple, as teachers in a secondary school. This would be an easy placement and common for married PVC’s.

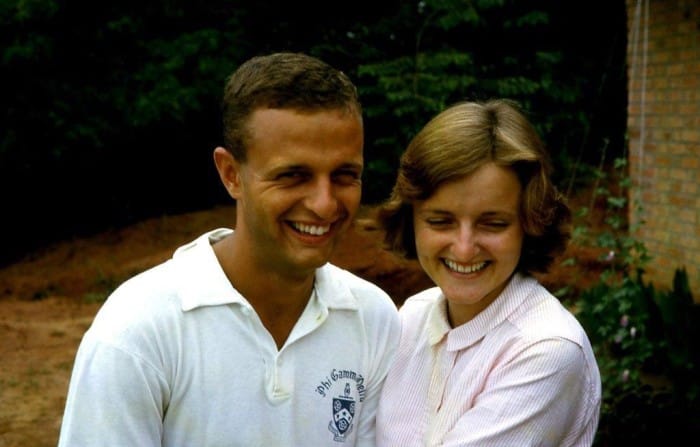

Tom and Ruth Nighswander as Malawi Peace Corps Volunteers in 1964

But a placement clerk had another idea. How about a public health project in an old British Colonial Protectorate that was soon to become Malawi? The decision changed their lives. He became a Doctor which he never even thought about in college and his wife who graduated with the elementary education German degree would become a nurse.

Yes it was I and my wife, Ruth. Now 50 year later this country continues to impact our lives. We have been back annually for the last 15 years and had an opportunity to live and work here for a year in the mid 80’s with our daughter attending standard four in her school uniform and our two year old son playing with our cook’s children in the back yard.

How much has changed in Malawi in all those years? You get a clue at 35,000 feet as you fly over this part of the world coming from the north. The flight takes one over the East African counties of Kenya, and Tanzania, and included a quick passenger stop in Lusaka, Zambia. What you notice from the ground are these points of light, which first appear as small mirrors reflecting the sun, but on closer inspection are in fact metal roofs on traditional village homes. They are still made of sun dried bricks in many places, but more and more often soft fired village-made more substantial bricks, and on the higher end homes, covered with stucco with a fine layer of Portland cement.

But when you get to Malawi air space, the point of light disappears. Yes a few more than years before, but a marked decrease from the nearby countries. Iron sheets for roofs have yet to reach the grass roof village houses that were the standard all over Africa years ago.

We work in a rural area in Malawi, and a visit to some of the more distant off the road villages is a trip back to the Malawi we first got to know in 1964. Much appears the same as it did then. In fact 50 years ago the population was much smaller, the fish and firewood for cooking more plentiful.

The main roads are well paved, Cell phones are everywhere (but reliable internet is iffy). Infant and under five mortality rates are half of what they use to be. But having adequate year around food and easily available drinking water are challenges. We are usually here in the January to March time period. In Chichewa it is known as the Njala (hunger time)

This is a subsistence culture, completely dependent of the once a year rains to raise maize.

Ground fine and cooked to a thick paste, the maize (nsima) is eaten with your fingers twice a day, 365 days a year. Dipped in a sauce of chicken or beans, Ruth and I find it quite tasty once in a while.

But harvesting a year’s supply of maize, with increasingly unreliable rains with in the first three months of the year, is becoming a national crisis. And we have been here when our village neighbors are out of food.

Yet today as I write this I am on the shore of the 10th largest fresh water lake in the world. Lake Malawi, one of the three great lakes of Africa, is a third of the country. But there is no irrigation. It is beyond the means of the villagers living in generally what is ranked as the 5th from the bottom poorest county in the world.

Board member Tom Nighswander visits the Open Arms Infant Care Home during the Nighswanders recent annual trip to MCV.

And then there is HIV/AIDS. It ransacked the country. At the height of the epidemic, the police and military were down 40% from their full strength manpower. HIV/AIDS does not discriminate. It affects all ages, but is especially devastating to the 18-38 year old- the future of the country. Anti Retro Viral’s (ARV’s) , the mainstay of treatment, first appeared in the northern hemisphere in the last part of the 80’s, but did not start showing up in this country until 2005.

The by-product of the epidemic has been thousand of orphans. With one or both parents gone, the task of rearing these kids has gone to the grandparent or other caregivers in the village.—another child to feed, provide clothes for and send to school.

Can you make a difference? The epidemic developed for a complex reason. It is a result of poverty, woman empowerment, literacy, easy access to adequate health care, a government that denied HIV existence until the mid 90’s and I am sure there are others.

But when you break the epidemic down to the village level, then there are many interventions that make sense. This was the approach which a group of Malawians and one former PCV from the late 60’s conceived in 1997– the Malawi Children’s Village.

For 37 villages surrounding a core campus of a vocational training and secondary school, the focus was the plight of HIV/AIDS orphans. At the crest of the epidemic there were 3000 out of a total population of 30,000.

With the program in place, if you were an orphan caregiver you received assistance with food, clothes, improved houses, and school fees. Added to the program over the years was a bed net program for children under five (reducing the malaria rate by 70%) . The Engineers without Boarders, Alaska Chapter, installed a safe water program on the core campus with plans to connect to the nearby villages. Six Anchorage primary schools formed partnerships with primary schools in the catchment area and provided resources for pit latrines, teacher housing, desks and supplies.

The results– orphans who would have never had a chance are now teachers, clinical officers, agriculture and social serviced workers.

It does not get much better than this.